The Rabbit

In the Rabbit Cage

I follow Madeleine as she walks through the grass in front of me. I‘ve asked to see her rabbits. What looks like a large cupboard leans into the back of the stone building. As we approach, I can see little cozy cubbyholes and, as I look more closely, I take in soft black and white fur and constantly twitching noses. I want to poke my finger through the chicken wire and touch them but Madeleine warns me. “They might bite,” she says. But she is already taking one out, cradling its furry body in her arms, and letting me stroke its soft pelt. “So this is where the rabbits live,” she tells me. “I’ll send one home with your family.”

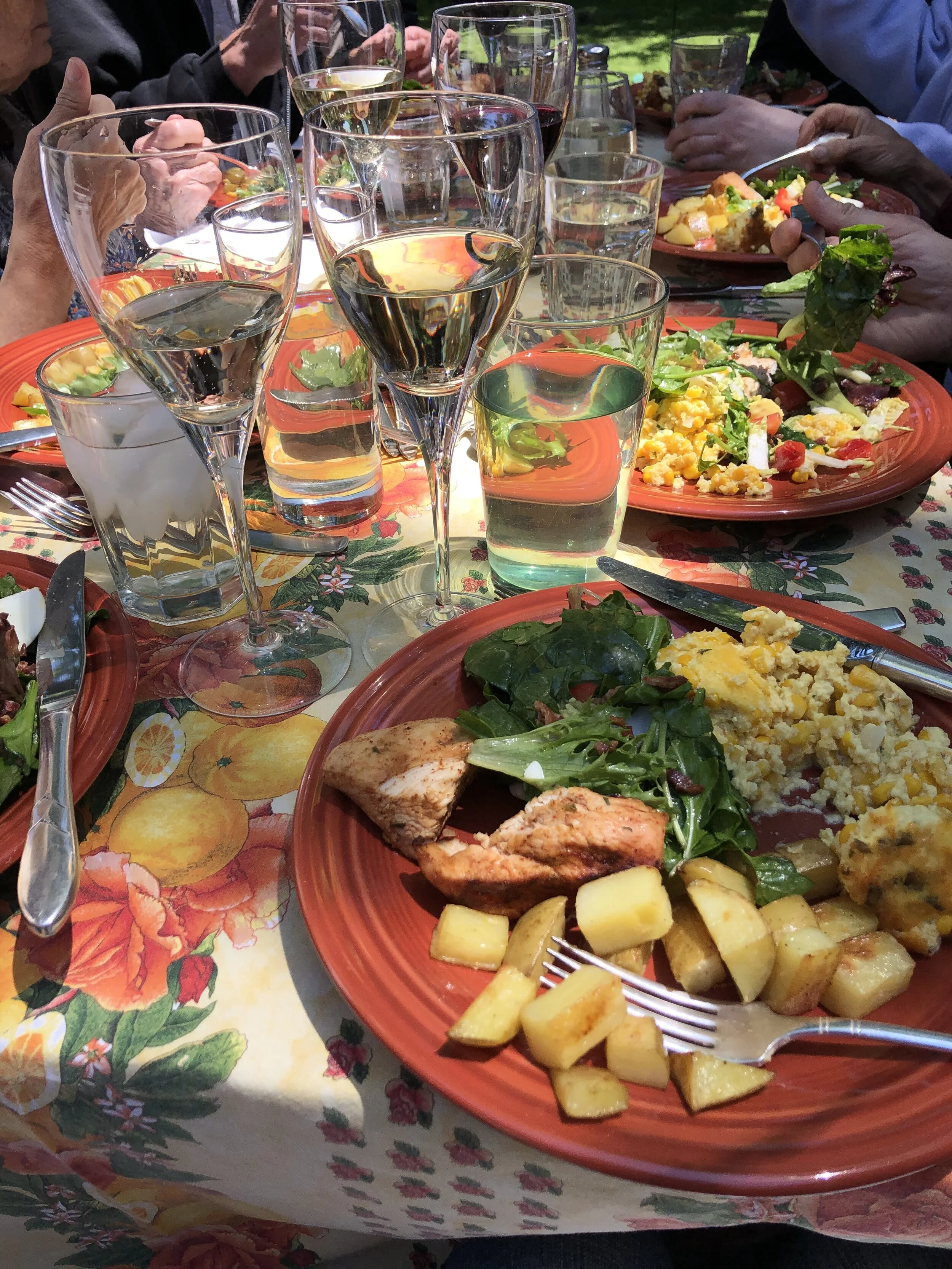

Madeleine and her husband, Jules, are friends and colleagues of my parents. They live on a large estate in southern Belgium that houses a retreat center and where Jules publishes books. Every now and then, we drive the one and a half hours to visit them. My father and Jules usually have business to take care of and sometimes I tag along into the office so I can hear their adult conversations. But I also like to follow Madeleine around in her large bright kitchen as she cooks and prepares the meal we will share. Today, she is making braised rabbit with prunes, a classic dish from her childhood in France. Even though I’m a tall 11 year old, Madeleine is not much taller than me. Her dark hair is pulled back off her face but wisps of it escape as her hands tirelessly work. Her dark brown eyes don’t miss a thing as she chops the rabbit, braises it then adds seasonings. I help to set the table with the guidance of her sharp, chirping voice. I can tell that Madeleine knows how to run this place. When the meal is served, it’s semi-formal, with china dishes and cloth napkins. And the rabbit is so good. That’s when I find out that they raise rabbits and I ask to see them.

Cooking rabbit in Provence

As promised, Madeleine gives us a rabbit to take home, not the furry kind I saw out back but the now lifeless, skinned kind. My mother is excited to cook it and try Madeleine’s recipe. When she opens up the package in our kitchen, she discovers the rabbit still has its head. She can’t make herself chop it off. So she calls my sister and she calls me and she calls my brother. We all stand and look at the rabbit. We all take the knife, raise it and then drop it. We remember the living rabbits in their dens. We can’t make ourselves chop off this one’s head. We remind ourselves that this is now just a piece of meat. Finally, one of us takes a deep breath and lets the knife do its work. The head is off! My mother cooks up a delicious dish but as I taste each bite, there’s a tinge of bittersweetness.

These days when I cook meat, I try to remember the whole picture. The dish on my plate is not just meat; it started out as a living being made of fur or feather. And it should receive my reverent handling as I prepare it. Whether animal, vegetable or mineral, I want to eat my food with respect and be thankful for the life it keeps giving.